Relatives, public gather for ringing of ship’s bell each November

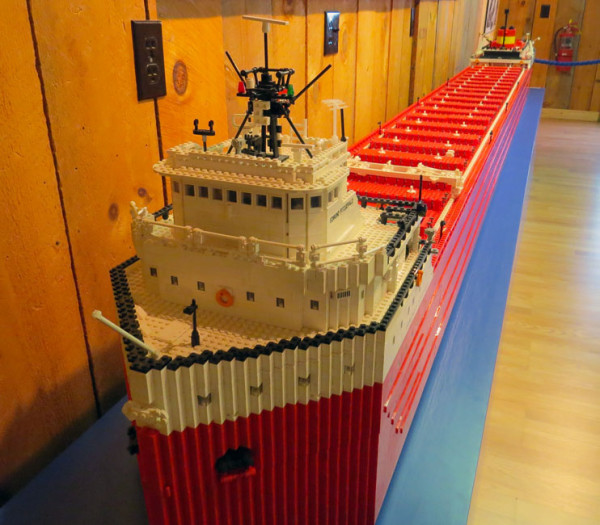

The story of the Edmund Fitzgerald has inspired song, prose, and art including this 18,000 piece 1:60 scale model by high school teacher John Beck. The project began in 2004 to teach his students about shipping. Nine years later it is almost complete.

Most upper Midwesterners know the story of the Edmund Fitzgerald, a lake freighter that sank in Lake Superior in boiling waters kicked up by a snowy gale around 7:15 p.m. on November 10, 1975. The mystery surrounding its sinking has entranced people far and wide since it was only 17 miles from the safety of Whitefish Bay when the ship met its end.

Each anniversary of the sinking, relatives of the 29 people lost on the Edmund Fitzgerald, in addition to locals, and the curious but reverent general public; crowd into the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum’s shipwreck exhibit at Whitefish Point to memorialize the event in a somber ceremony.

I attended the event in 2012 and had a chance to talk with two family members about the men that they knew on the “Big Fitz”, plus witness the ringing of the ship’s bell which was retrieved from the sunken wreck in 1995.

The lore of that event was a big part of my childhood since the boat sank only 30 miles north of our family summer cabin on the southern shore of Whitefish Bay in the eastern Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

I was only two at the time, but most nice days we can see Canada from the beach as well as boats passing through the bay as they start or finish traversing the largest and most unforgiving of the Great Lakes.

At the 2012 Fitzgerald Memorial Ceremony, the 37th anniversary of the sinking, Cheryl Rozman and Ruth Hudson talked to Willy Street Blog about how they learned their family members were missing and what their experience has been since then; as they tend to the memory of the men who were lost, under a worldwide spotlight.

Rozman was the daughter of Watchman Ransom Cundy and was not surprised that her father was on a late season run since they would not see him until the shipping lanes were frozen solid. Ruth Hudson, whose son Bruce was a Deckhand and worked in Maintenance, said he told her earlier that summer that the motorcycles he rode were not dangerous and that instead he would die in famous way.

Interview – Fitzgerald crew relatives Cheryl Rozman and Ruth Hudson

[jwplayer player=”1″ mediaid=”5567″]

The Fitzgerald was named for the President of the Milwaukee-based Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company and entered service in 1958. It sailed the lakes for years as the largest boat out there, setting some speed and tonnage records along the way. In early November 1975, it left Superior, Wisconsin with a load of iron ore for one last run to Zug Island in the Detroit River. The island is at the mouth of the Rouge River, home to Ford Motor Company’s massive Rouge River plant.

Whitefish Point, looking east. To the right, the relative safety of the bay. To the left the eastern end of the “Shipwreck Coast”. Seventeen miles to the north, the final resting spot of the Fitzgerald.

The Fitzgerald couldn’t quite outrace a mega storm that had its beginnings in Oklahoma but intensified as it arrived over Lake Superior on the night of November 10. One theory is that the Fitzgerald, while taking a northern route to avoid the heart of the storm, briefly ran aground on some shoals near a collection of islands in the northern part of the lake three hours earlier. From that moment on, the ship began slowly taking on water before enormous waves finally did her in.

Another theory is that a mega wave dipped its bow under and it struck the bottom of the lake and snapped in half. The Fitz measured 729 feet, 200 longer than the lake is deep where it sank. But no definitive cause has been proven, even by the ardently meticulous National Transportation Safety Board.

The U.S. Life Saving Service helped turn the maritime sailor from a deadly adventure to a relatively safe occupation.

In the 1800s and the early 1900s around 3,000 ships plied the waters of Lake Superior, most of them were wooden and suffered collisions or succumbed much easier to the lake which is often referred to as an inland sea.

In those days shipping was a precarious endeavor. Navigation was still an evolving science as lighthouses every 20 miles or so showed the way as ships hugged the southern shore.

The open lake often unleashed its full fury and the stretch from Munising in the central U.P. to Whitefish Point became known as the “Shipwreck Coast”. Now only about 250 freighters handle all the shipping.

Being a lighthouse keeper was nearly as dangerous as the lack of roads in the stark regions around Lake Superior meant all resupply was by ship. It was a lonely existence even though keepers were allowed to live with their families.

Early lifesaving involved firing a messenger line via projectile from a Lyle gun (cannon). Then a larger line on the spool in the rear of the cart is attached for towing or ship-to-shore crew transfer.

By the 1970s, the fact that such a modern lake boat would sink during a time when shipping had become more routine than adventure, has fascinated both maritime enthusiasts and anyone else who has encountered the story of the Fitz.

Terry Benosh, site manager of the GLSM says the story of the Edmund Fitzgerald brings people to the museum from around the world.

“People seem to get emotionally connected to the story, part of that is attributed to Gordon Lightfoot’s song…but their imagination is just captured.”

A stop at the GLSM north of Paradise Michigan is a must if passing through the U.P. for a surprising look at the evolution of shipping, navigation, and the U.S. Life Saving Service that involved large rowboats, and even cannons.

Interview – Terry Benosh, Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum

[jwplayer player=”1″ mediaid=”5568″]

The Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum on the grounds of the Whitefish Bay Lighthouse. Live-in keepers left in the 1930s as now only a small but powerful electric light and radio beacon have replaced the oil and kerosene fired lights of before.

Terrific story! You are right, the GLSM is a fascinating place, full of history and information about our “inland ocean” neighbor. Thanks for this.

Bruce I am sorry only you know what I am talk about! RIP GOD BLESS YOU