Police shooting highlights shortcomings in our progressive culture

Friday was the day we all realized that our neighborhood, which over the decades has changed for good in many ways, really hasn’t changed at all. Sitting with family and friends for dinner at Take Five, we saw an urgent parade of police vehicles pass by, seven in all.

It is normal to see ambulances and fire trucks on this important artery through the Near East Side. But this was different; we knew a serious situation was occuring when so many police are the first to rush by.

A regular patron headed down the street to investigate and reported back that shots had been fired in the 1100 block of Williamson Street. His information was rushed and proved accurate on only two points: that someone had been shot and that he saw CPR being peformed on an individual before an ambulance took him away.

I say “him” because it was Tony Robinson who was killed during a scuffle with a Madison Police officer. His eventual death has displayed in very stark terms this city’s continued struggle with race, police deadly force protocol and access by our minority communities to Madison’s perennial “Best Place to Live” status.

“I think the community is in shock, frankly. Because of what has happened in the past, in spite of this being one of the more progressive communities in Madison. I think the community has come to the realization that Ferguson is really not that far away. It is literally around the corner from my home, where my 18-year-old son and I live,” Hanah Jon Taylor told Willy Street Blog as he and his son Gabriel stood across the street from the site of the shooting Saturday morning.

The home where Tony Robinson was shot. The altercation took place when Officer Mike Kenny forced his way into the side entrance on the left.

“And so that’s something I’m alarmed about as a community member. I talk to my son about it all the time. He definitely has the talk, and now he sees face-to-face, first-hand, why the talk is necessary.”

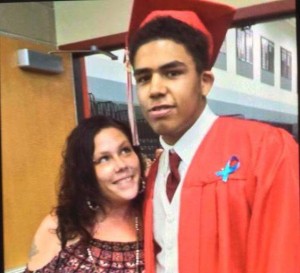

By many accounts, Tony Robinson was a promising young man, who did have a felony robbery convcition but had plans to do better and pursue education beyond high school.

Court documents say he was diagnosed with anxiety, ADHD, impulsivity and other related mental conditions. This complex picture makes it hard to judge him; certainly not for a split second just inside an apartment hallway by an armed police officer.

“This is something that we are going to deal with for the rest of our lives,” Robinson’s Uncle Turin Carter said at a Monday press conference. “We don’t think Tony is a saint. He has made mistakes. That is completely disassociated with this act.”

But based on the history of black men dying at the hands of police in America and the social media reaction to Friday’s events, the color of his skin seems to loom large when judging Tony Robinson.

“I was just surprised. I was in shock. It’s hard like for someone to just pop up, right around the corner and I’m like, I’m just a year younger, I’m only 18. So it’s like, dang, I’m, like, an endangered species now, I gotta really watch out for these guys,” Gabriel Taylor said.

The Taylors lived a few blocks away on Willy Street when Gabriel was very young. Gabriel didn’t know Tony but knew his family, and they likely would have been friends.

“I’m sure we would have been really cool friends, like if got to know him around the neighborhood.”

But he adds Madison and its police department have work to do to earn the trust of young black men like him.

“Madison has always been like pretty sweet, you know. It’s just weird, a couple weeks ago, we had a shootout over at West Towne mall and now this is goin’ all -it’s like one thing after another. Things are gettin’ crazy out here and the police are a part of it, because they are the biggest gang in the world. People need to know that, you know.”

The Madison Police Department, under the new direction of Mike Koval, has made pains to appear engaged and conciliatory since the shooting took place. Koval met with Robinson’s grandparents that night and has since talked with his mother.

Koval has also consulted leaders in the minority community, such as Boys & Girls Clubs of Dane County CEO Michael Johnson, from the outset, who have supported his moves so far. And Koval has publicy apologized for Robinson’s death on his blog.

However, that doesn’t change the fact that our police department has a judgment problem when it comes to use of deadly force.

Despite a peaceful resolution early Friday morning after Tommie Evans fired a fusillade of bullets at eight officers, Robinson is the latest of several people to be killed by Madison police since November 2012.

This is the second time in this neighborhood that a troubled man has died in this way, as the memory of Paul Heenan is still fresh in our minds.

Heenan’s death is one of the reasons this incident will be investigated by a third party, thanks to a recently passed law put forward by the neighborhood’s state representative Chris Taylor (D-Madison), who coincidently was across the street pumping gasoline when the Robinson shooting took place.

Williamson-Marquette: A place for all people

My ethnic makeup is half European and half Lebanese. While during the summer months I can be the envy of sunbathers, I appear white and have mostly benefitted from white privilege. On 9/11 I was flying passengers from Wisconsin to Pennsylvania during those harrowing hours. Save for an ugly incident at the U.S. border at Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan while on vacation in 2003, I have not experienced overt racism due to my name or appearance in my personal or professional life.

I grew up on Willy Street, beginning over forty years ago, knowing it as a caring and welcoming place. It still is, but along our path of good intentions we have allowed too much gentrification. The underserved and underemployed, who in the past have found refuge in our area, now often find our housing and institutions out of reach.

We have built a veritable utopia of fresh foods, festivals and community organizations and services. So why is progressive Madison still having such a problem with race? Because we built this utopia too much in our white image, devoid of the flexibility to allow access by minorities to help shape its framework.

I have had many African-American friends from varied backgrounds while growing up. Delwin lived in the apartment behind my house when I was about ten. He didn’t stay around long, but we played together often.

Mary Millon and her younger brother also lived in the neighborhood. They were adopted by white parents who also had two kids of their own. Our two families gathered often over our lifetimes, and we still are close.

During my last years at Madison East High School, my closest friend was David Hart. We were opposites politically, but felt that no topic was off limits when it came to satirizing people and things we saw every day. The greatest thing David did for me was after I made a racist observation about a group of students one day.

Within a day or two he had arranged a meeting with himself, me and a school counselor to address my characterizations. My first reaction was incredulity, but then I realized that my words really hurt and went beyond our accepted boundaries. David is now a Madison lawyer and chairs a City of Madison committee.

That episode serves as an example of the unconcious things we say and do that deeply affect others. Whether it is asking to touch a black woman’s hair, building developments in the central city that only offer market-rate rents or never attending a cultrual event outside your comfort zone.

All of my friends mentioned above, save for Delwin, had economic and parental support systems similar to my own. But I will never know what it feels like to almost constantly brace for some sort of bias, unconcious or intentional, when interacting with white people. It is a cultural “walking on broken glass” that most in our community never have to worry about.

“Being an African American in this community, even 29 years ago when I was a freshman in high school, I didn’t feel we had ever experienced the racism that is happening right now in 2015,” Millon said.

A former school board member told me that during my time in high school (1987-1991), minorities made up approximately 20 percent of the Madison Metropolitan School District’s student population. Now the minority student population is 55 percent, yet we as a community still have not adjusted ourselves, our organizations, or our govermental institutions to this population shift.

In my time, it might have been less threatening to white students to assimilate the few minorities present. I also think that many of my fellow white students just didn’t care. East High even then had a higher minority population, and it was just the norm. But the community at large still hasn’t taken the hint or doesn’t understand how to.

“You see, there is no reason why African-American men of any age should be afraid of the police department of their city. But you see this is what happens, this is the result of poor communication and maybe poor community work on the part of the police,” Hanah Jon Taylor said.

“You know we see the police a lot when there are a number of African-American men around, but I can tell you you can walk two blocks toward the lake where I live and we hardly ever see any police, okay, and I’m the only black man around. Me and my son.”

Let the children lead us

Nearly 1,500 students protest the Robinson shooting at the Wisconsin State Capitol, March 9, 2015. (Via twitter)

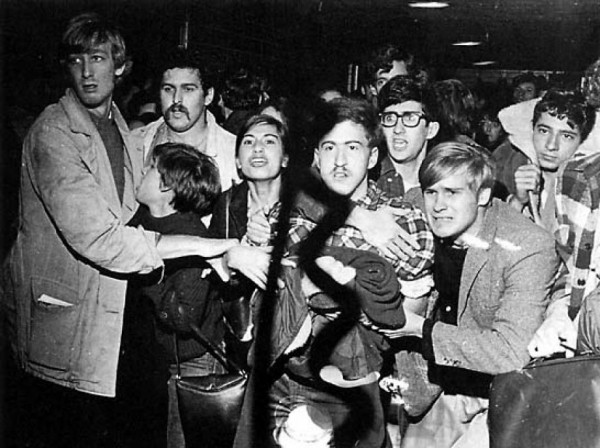

In October 1967, a plucky young activist from Chicago, a bandage on his head from the beating he took from Madison Police during the Dow Day protests the day before, stood atop Bascom Hill in front of legions of his fellow University of Wisconsin students and called for a general student strike.

It was none other than Paul Soglin, who has been a part of Madison’s fabric ever since.

In the late 1960s and early ’70s, it was young students challenging the societal status quo that lay the foundation for much of what is good about Madison today. The Willy Street neighborhood is a direct outgrowth of those strong and often unbending pushes for change. Many of those activists are now the elder statespeople of the area.

I found it striking to see the image of Soglin Monday, addressing 1,500 Madison area high school students as they occupied the entire portion of Martin Luther King Boulevard in front of the City-County Building. In Soglin, the students so far have a sympathetic ear, but he and the rest of the city must realize these young people are prepared to push hard for a racial renaissance.

This effort is being led by the Young, Gifted and Black Coalition, which has been agitating for changes in local policies, especially around policing and incarceration rates. The group, led by Brandi Grayson, was on the scene of the shooting within hours.

“I think it’s powerful, I think it’s important,” said Kareem Caire, a local community leader. “Brandi Grayson is my cousin. I’m proud of her for comin’ out here with all the other members of that group to advocate. People are all like, ‘you can’t rush to judgment.’ Well, you know, our young men are getting shot all over the place, what do you expect?”

Paul Soglin (far right) pulls up his sheepskin-lined coat as he prepares to be beaten by Madison police who used night sticks to clear the Commerce Building at the request of the UW Administration.

“I’m so glad they took it upon themselves to come out here and get other people, because that’s one of the ways you keep people from blowin’ up, is you give them an outlet to let that frustration [out] and also to figure out what happened.”

One might have have been taken aback to see protests at the scene of a shooting before all the facts have been released.

But our minority communities are tired of waiting around for facts and then not seeing any changes. Plus, whose facts are they? The protests, vigils and marches in the past few days are just the kind of truth to power that is needed in Madison.

The adults in this city have tried, but meetings, symposiums and op-eds have yielded glacial progress. In just a few short days, unfortunately born out of tragedy, the young people of this city are the ones demanding changes. Our elected and community leaders have begun to listen.

We all owe our child-citizens results.

Related: A Terrorist Gave Me Lemonade

Related: Heenan Shooting Report Released

What a terrible situation, and thoughtful response. Thank you for writing this.

I’m glad there is a law requiring a third party investigation of what happened.

Seems like there’s been a rush to condemn the police officer. What if it’s true that Mr. Robinson attacked the officer and he had reason to fear for his life?

Regardless of the outcome of the investigation, race and equality in the city must be addressed.